Every so often a Canadian government, peeved with its continental neighbour the United States (US), and carried away by fits of anti-Americanism wrapped in a nationalist cloak, will try to convince Canadian businesses to diversify trade to the UK or the European Union (EU). It was attempted under Progressive Conservative John Diefenbaker in the 1950s, it was attempted under Liberal Pierre Trudeau in the 1970s and early 1980s, and it is being tried once again by Liberal Mark Carney. Carney’s goal is to steer the nation toward deeper integration with the EU ostensibly to reduce reliance on the US, Canada’s largest trading and defense partner. The “Enduring Partnership Statement” signed on June 23, 2025, alongside initiatives like the Canada-EU Green Alliance, the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), and discussions on a joint industrial strategy, indicate a policy pivot. However, closer ties with the EU also mean alignment with, if not adoption of, the EU’s stringent climate and Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG) regulations, like the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), and the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), all of which impose heavy compliance burdens that could undermine global Canadian competitiveness. Indeed, as the European Union ties market access to an ever-expanding web of costly non-tariff barriers, Canadian exporters must ask: at what point do the “strings attached” become shackles?

Let’s take a closer look.

Trade-offs and the Risks of EU Alignment

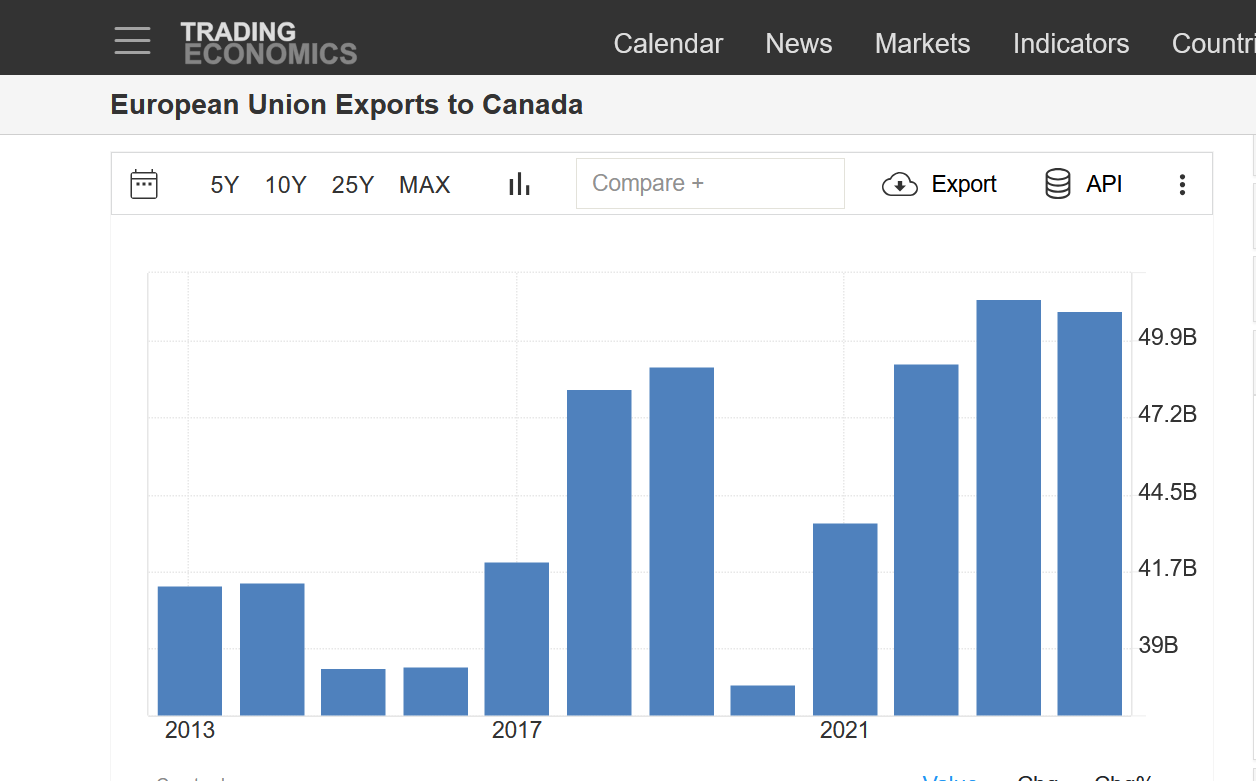

The Canada-EU Summit in Brussels on June 23, 2025, symbolized a step toward a “new, ambitious, and comprehensive partnership,” as outlined in the joint statement. Points 16 and 17 of the 22 listed in the statement, highlight CETA as being “at the core of the EU-Canada relationship.” However, CETA, which has been provisionally applied since 2017, has had mixed results: ten EU nations have yet to ratify the agreement and until they do, the agreement is provisional. EU exports to Canada steadily increased from 2017 until the Covid pandemic in 2020; since 2020, exports have reached and slightly exceeded pre-pandemic levels. For example, at the peak in 2019, total EU exports to Canada were $49 billion and since 2023 have hovered around $51 billion.

However, even though the EU has a significantly higher consumer base, imports from Canada are not equal and have not recovered from pre-Covid trade. Since 2017, imports increased slightly from $35 billion to $39 billion at the peak in 2019; post-Covid the value of Canadian imports have hovered around $29 billion. The trade gap between the EU and Canada has definitely grown in favour of the EU since 2021. Perhaps part of the slow imports from Canada into the EU is related to ten EU member nations not having yet ratified the CETA. Or perhaps it is due to the increased regulatory burden implemented as part of the EU Green Deal and its associated directives and mandates.

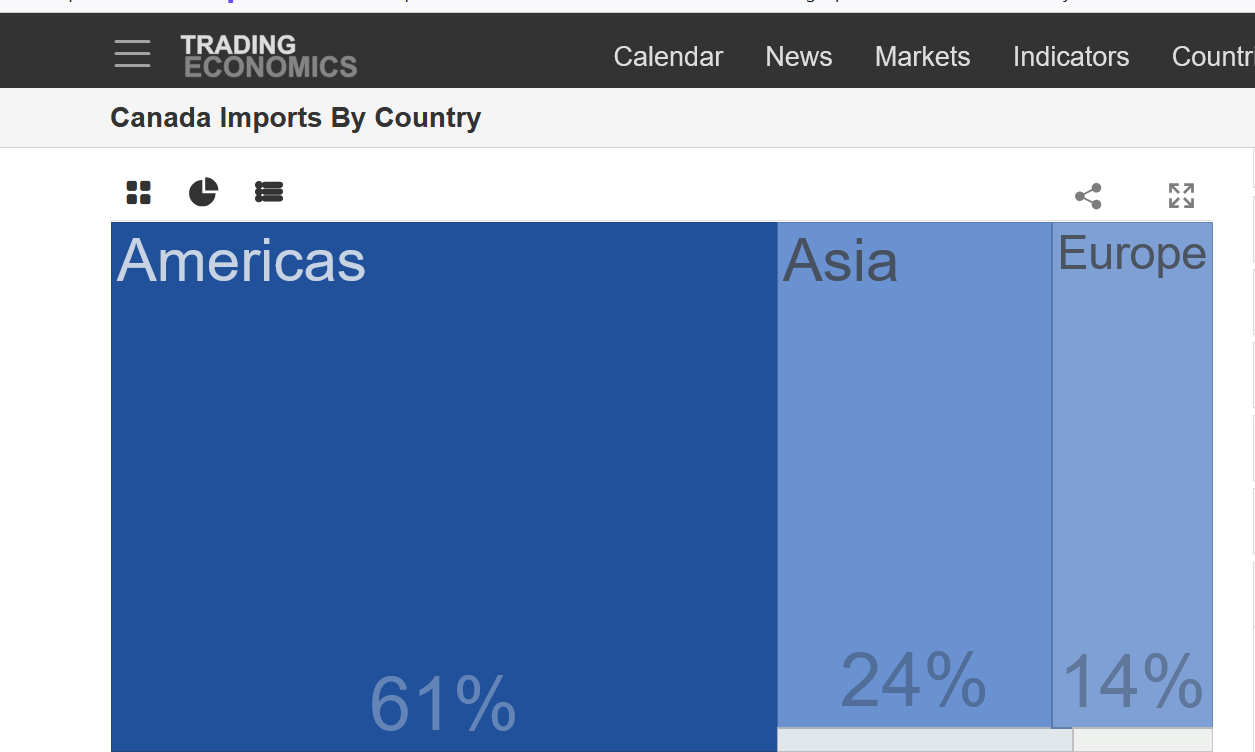

For context, this modest increase in trade between Canada and the EU represents a small portion of both jurisdictions’ overall trade. Looking at trade data for Canada from Trading Economics, in 2024, the combined EU nations represented 14% of imports into Canada with the United States and Mexico totaling around 61%, and Asia being 24%.

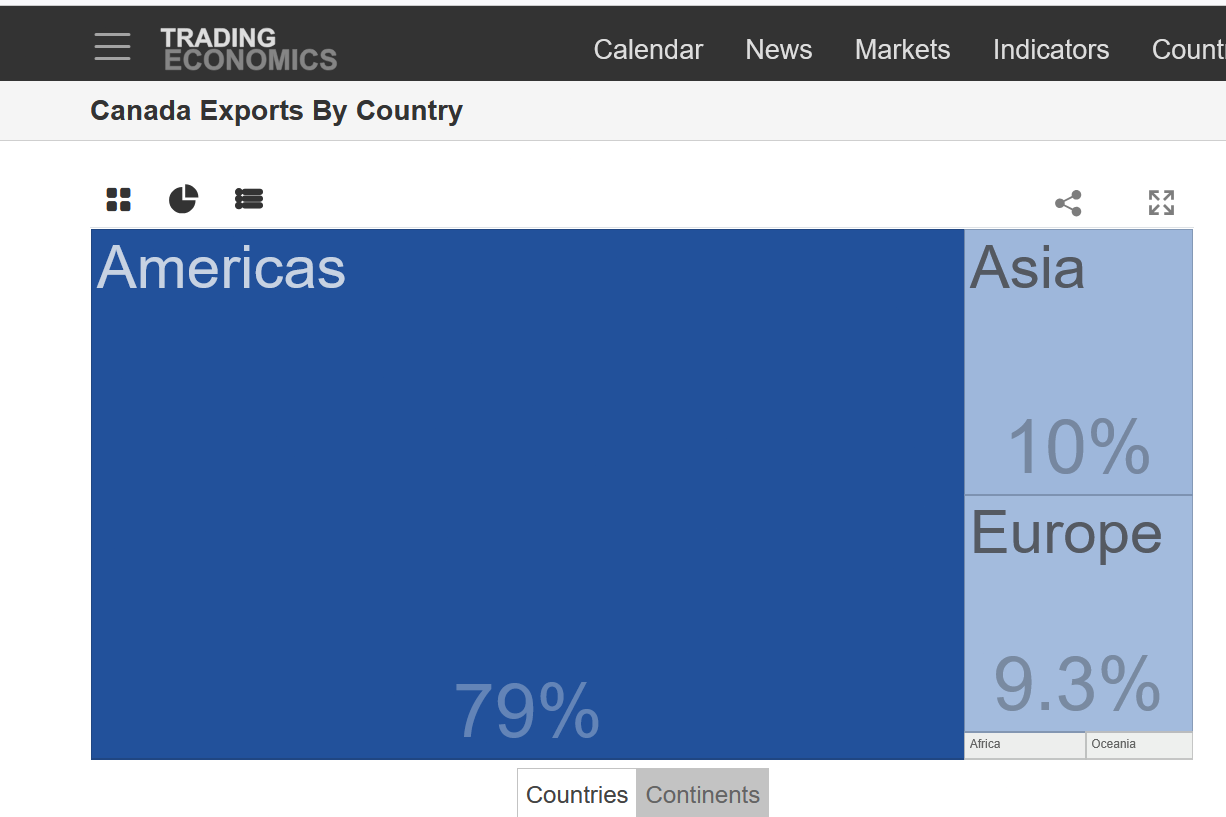

Canadian exports to the United States and Mexico are 79%, Asia is 10% and the EU 9.3%.

Is there room to increase? Yes, indeed, but at what cost?

Closer ties with the EU come with strings attached. The EU’s regulatory framework is shaped by its net-zero agenda and demands alignment from Canadian businesses seeking market access. Regulations like the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), and Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) impose rigorous requirements on environmental performance, supply chain transparency, and emissions reporting. But these policies, while noble in their rhetoric, amount in practice to a powerful barrier. Instead of fostering fair, open trade, the EU is increasingly dictating terms that force Canadian companies to shoulder compliance burdens only the large can afford, especially in energy intensive industries already under threat.

Implications for Canadian Businesses

Trading with the EU requires Canadian companies to navigate a complex web of regulations. The CSDDD mandates due diligence on environmental and human rights impacts across supply chains, affecting even smaller Canadian firms supplying larger EU partners or even larger Canadian companies that are subject to the regulations. The CSRD requires detailed sustainability, climate, and nature reporting, adding further administrative burdens. Although the EU has scaled back some of the requirements due to push back from SME’s, the compliance burdens remain for large companies and their supply chains. The CBAM, set to tax carbon-intensive imports in six key industries, directly impacts high-emitting sectors like oil and gas, steel, and fertilizer. These regulations, while aligned with the EU’s climate goals, risk pricing Canadian goods out of the market and potentially making Canadian entities less competitive against American and Asian rivals.

For SMEs, the cost of compliance is particularly daunting. Unlike large corporations with dedicated legal and sustainability teams, smaller firms lack the resources to overhaul operations or supply chains to meet EU standards. The CETA Regulatory Cooperation Forum aims to align regulations, but as Mark Camilleri notes in Policy Magazine, progress has been slow; businesses have been left to bear the brunt of diverging standards and navigating complex regulations. Canadian companies may find themselves swapping the familiarity of U.S. markets for a more bureaucratic and costly EU alternative.

A further implication of closer ties with the EU, and the net-zero push, is point 15 of the Partnership Agreement which stated, “The EU-Canada Green Alliance is our steadfast, joint commitment to ambitious environment and climate action on the global stage.” Why is this important? The Canada-EU Green Alliance, prioritizes “carbon pricing, carbon removal and industrial decarbonization…and a high-integrity carbon market…” The Green Alliance is also committed to reducing methane emissions by 30% by 2030 and phasing out unabated coal. By affirming the principles of the Green Alliance in the EU-Canada Partnership Agreement indicates that net-zero is still a core motivating principle in the EU, its regulatory framework, and its trading relationships. It is difficult to reconcile these climate commitments with the coy talk on potential oil and gas pipelines in Canada that Prime Minister Mark Carney has been making to mollify Alberta and Saskatchewan since his election in April 2025.

Mark Carney’s climate credentials, as a former UN special envoy on climate action, suggest a subtle but pervasive integration of climate policies into Canada’s regulatory framework, as noted in Canada’s National Observer. While Carney avoids explicit climate rhetoric, his policies—such as Bill C-5, rushed through to counter U.S. tariffs—embed climate considerations into economic decisions. For Saskatchewan’s and Alberta’s oil patch, promises of new pipelines under Bill C-5 may be a temporary concession to secure political support, but the broader trajectory points to decarbonization over expansion and will likely rotate around mandatory emissions accounting, taxation through an enhanced industrial carbon tax, and the implementation of a Canadian version of a CBAM.

Weighing the Trade-Offs

The pivot to the EU is not driven by economics but rather a reflexive reaction to US President Trump’s tariffs on Canadian trade not covered under the US-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA). The benefits of increasing trade and deepening relations with the EU seem to be few and far between. Maybe it will mean increased Canadian access to EU financing, participation in the EU defence rearmament scheme, and moral support for climate and environmental initiatives. However, the costs of this shift are steep. Canadian businesses face a trade-off: access to the EU’s 450 million consumers versus the burden of compliance with its complex onerous regulatory regime. For high-emitting sectors, the EU’s climate policies could lead to reduced market access, higher costs, and domestic deindustrialization, while SMEs risk being squeezed out by administrative demands. While the EU’s market is large, it is far from the only game in town.

In contrast, US markets, despite tariff threats, offer a less regulated environment and proximity advantages. The United States remains Canada’s top trading partner by a wide margin, and the North American market is more than an economic convenience—it is an economic integration that has been cultivated over decades of shared relationships, culture, and free market attitudes. The U.S., despite its own periodic tariff threats, still offers a more familiar, accessible, and often less regulatory compliance-driven marketplace for Canadian goods. The USMCA framework, though imperfect, delivers a degree of predictability and shared regulatory culture that the EU simply does not. I asked X-Ai’s Grok to break down the costs of various Canadian sectors trading with the EU versus the US. In all of the examples, the average across sectors was 3-10x higher EU costs compared to trading with the US due to regulatory and logistics burdens.

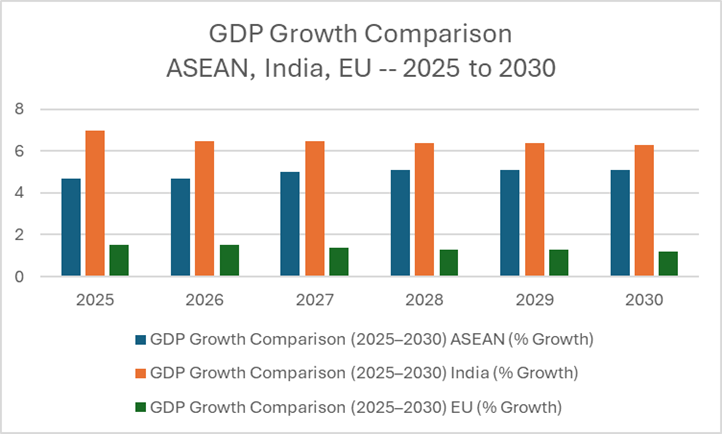

Beyond North America, Asia’s burgeoning economies—from Japan and South Korea to the vast consumer bases of Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam) and India—present immense opportunity without the regulatory gauntlet imposed by Brussels. Indeed, according to data compiled from S&P Global, Statista, the IMF, and ADB, the Southeast Asian region is also projected to lead the world in economic growth over the next five years, while the EU’s economic outlook is stagnant.

The critical question, then, is not whether Canadians can comply with EU rules and create similar ones, but whether they should. Is it wise to invest millions—sometimes billions—in bureaucratic reporting, supply chain policing, and carbon accounting, all to access a market that is, itself, struggling to maintain competitiveness? Canadian businesses must carefully assess whether the EU’s market potential justifies the compliance costs, especially when competitors face fewer barriers elsewhere. Furthermore, other markets in the ASEAN region and India are hungry for Canadian resources, food, and expertise. They don’t demand endless layers of customs and sustainability documentation; they want reliable partners and quality goods. By focusing on these alternative markets, Canada can reduce its exposure to single-market risk, diversify its trade portfolio, and maintain the flexibility to chart its own regulatory and industrial course.

A Path Forward

Canada’s alignment with the EU offers opportunities for diversification but demands an honest and realistic assessment of costs. Canadian policymakers ought to rethink the assumption that deeper EU engagement is always desirable. The priority for Canada should be strengthening North American supply chains, leveraging the USMCA’s foundation, and aggressively pursuing opportunities in Asia where the cost of market entry is not a slow bleed of compliance, but a genuine chance to compete and win.

That does not mean turning away from European values or ignoring global environmental standards. But it does mean refusing to let European policymakers alone dictate the terms of Canadian prosperity. Canada’s economic future should be built on opportunity and diversification, not on the illusion of partnership that asks Canadians to pay the price for Brussels’ ambitions.

Conclusion

The EU is undeniably an important partner—there is a lot of history between Canada and the EU—but it should not be allowed to become the gatekeeper to Canadian prosperity. As other trading blocs offer growth with less red tape, Canada must weigh the real costs of compliance against the very real opportunities elsewhere. Rather than crumbling under the administrative and economic burdens of alignment with Europe, it is time to look west and yes, to the south—and across the Pacific—to partnerships that celebrate, not stifle, Canadian innovation and industry.